Until late in the 20th century, tequila was almost always crystal clear or pale gold, with the hue coming from brief aging or allowed additives. Those tequilas, generally mixtos rather than the 100 percent blue agave so popular today, were produced in a fairly straight-forward process compared with most of the world’s spirits – fermented, distilled and then bottled right away, or after a brief period rested in barrels or tanks.

That’s it; no concerns about sourcing, storing or managing barrels, controlling temperature and humidity in aging warehouses or determining specific barrels for blending into aged expressions. In many cases, distilleries simply dumped and bottled without much regard for consistency batch to batch, leaving a small footprint for the aged tequila market.

While most of the growth of tequila has been credited to consumer’s interest in the pure agave varieties, many have instead been drawn to the steady rise in quality evident in the spirit’s aged expressions. These are the tequilas that, as the worldwide boom continues, gather attention in many countries, as well as in the U.S.

The single component that differentiates good from great aged tequila is the wood used to age the spirit. The impact of the quality and previous usage of the wood cannot be overestimated, as Dr. Bill Lumsden, head of distilling and whisky creation at The Glenmorangie Company, told me last year about a different spirit. “I say to people all the different parts of the process are important, from the source of water to the choice of raw materials to a well controlled distillation. But at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter how good your spirit is; if you don’t have good quality oak, you simply can’t make good whisky.”

The same holds true for reposado, añejo and extra añejo tequila – what separates good from great is quality oak and how it is treated.

Of course, many houses “age” their blancos as well, which among other things is an increased cost, even if aged less than the two months that are allowed by the Consejo Regulador del Tequila (CRT).

“To fill those warehouses with barrells takes time,” says Herradura master blender Ruben Aceves. “It is an investment to make a 45-day blanco, when it costs much less to have a blanco that comes directly out of the still.”

A Recent Phenomenon

Commercially available aged tequilas are a fairly modern invention, with the first reposado not launched until 1974, although a number of tequila houses kept aged barrels at home for their own usage. But in every case, aging decisions start with barrel selection. Traditionally, Mexican distillers, like many of the world’s spirit makers, bought their barrels in lots from American whiskey producers who are required by law to use theirs only once in making Bourbon. In many cases, the containers were bought sight unseen.

Today, a greater scrutiny of barrels through arrangements made in advance with suppliers is the norm. And the choices are many, although in terms of expense, used whiskey barrels supplied by the largest U.S. producers (Jack Daniel’s and Jim Beam, for example) are most commonly in use. But some tequila producers opt for new oak barrels, whether American, French or even Hungarian in origin. Many determine the toast and char level of these customized oak barrels as well. Finally, in this case, size really matters – at least one tequila producer employs three different capacity barrels to age its tequilas.

For a brand such as Casamigos, it’s not the origin of the barrels that is important but the quality of each one, especially as the brand launched with a reposado first. Says Olivier Begat, VP of manufacturing and production at Casamigos, “Sourcing the once-used American whiskey barrels is all about choosing the right age of barrells, and maintaining a constant supply.” For their fairly new brand, Casamigos reps prefer making deals directly with suppliers rather than through brokers, in order to maintain a level of quality. In addition, they tend not to reuse their 200-liter barrels.

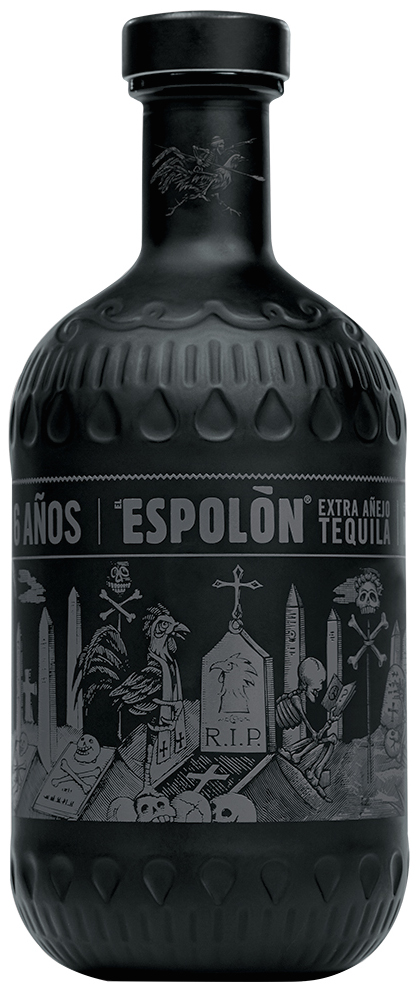

For other producers, how the barrels are prepared matters. For example, Espolon uses new American oak barrels with char level 2. Standard barrel char ranges from light to dark, one through four. Lighter char levels are said to impart more fruit and spice notes, while darker chars will provide more color and vanilla flavor.

“When our master distiller was creating Espolon, it was his desire that he always retain the purity of the agave, so he decided to use only new barrels for our aged variants,” says Christine Moll, marketing director for Gruppo Campari. “It’s a very important decision because it allows the agave flavor to be as pure as possible without the influence of other spirits.”

While opinions differ about how much impact previous usage imparts, master distiller Cirilo Oropeza’s main point was to limit influence to new American oak only, charred to his specifications. Espolon reuses the barrels, and throws in a little twist when it comes to its añejo expression; here, the tequila is aged for ten months in the standard barrels but finished for two to three months in ex-Wild Turkey casks made with a higher char (number four). Oropeza has said other types of barrels, like sherry, intrigue him.

“I love discussing barrels,” says Casa Noble founder and maestro tequilero, Pepe Hermosillo. For him, when planning the house’s aged expressions, he believed the industry standard high-char, used-Bourbon barrels wouldn’t fit his vision.

“Tequila already has a lot of character. We wondered what we could use that was better – in our case, we picked new French oak, which plays well with spices herbs and earthiness of our tequila by adding vanilla, nuts and fruits through the aging process,” he adds.

Patrón’s Antonio Rodriguez helps oversee quality control as production manager at Tequila Patrón, which employs a variety of barrels.

“Many brands use only once-used American whiskey barrels, and that’s the most common method,” he says. “We use new barrels made from French and Hungarian oak, as well as some very specific used barrels. The more types of wood and ages used, the more complexity in the final result.”

Rodriguez points out that not all reposados are necessarily aged in barrels, with some instead resting in large oaken tanks. As regulations allow for the addition of up to two percent of certain additives, some producers adjust the color of the final spirit to appeal to those who associate darker hues with age or quality.

Aged to Perfection

Herradura, which introduced the reposado style in 1974, ages its version 11 months – the CRT regulations states a reposado can be aged anywhere from two months to just less than a year.

“Producers aren’t required to state the age, and they can do just the minimum,” Aceves says. “The law regulates you must age a minimum of two months in a wood container and it can be the size of a building and not be a barrel. You don’t have to char or toast it or replace it ever if you don’t want to. It’s much more efficient to have a giant wood tank in your warehouse; it may not impart much color or flavor, but we are allowed to add some color or flavor to make it look and taste better.”

In the case of Patrón, the company’s newest line Roca Patrón differs in production methods (see the May/June issue of Beverage Dynamics for more about tequila ingredients and distilling methods).

The core brand is a blend of American, French and Hungarian oak barrels, with the reposado aged for five months, and the añejo an average of 14 months. For Roca Patrón, however, they use only ex-Bourbon barrels. Why?

“Roca has a huge agave complexity, and so we didn’t want to bring in more wood complexity. We were looking for mainly those vanilla flavors,” Rodriguez says. Patrón also bottles the spirits at different proof: Patrón’s core expressions are bottled at 80 proof, while Roca reposado weighs in at 84, and the añejo at 88.

“That higher proof delivers increased flavor complexity,” he adds. Higher proof spirits, of course, are more expensive to produce.

Numerous brands now use oak that isn’t American. Inaki Orozco, owner of Riazul, claims to be one of the first to use Cognac casks in producing añejo tequila, “And they are difficult to get and not inexpensive,” he says. For Riazul, he prefers Troncais rather than Limousin white oak. As he says, French barrels tend to be more expensive, with some reporting paying above $1,000 each, compared to used American oak casks costing in the hundreds.

Other brands use both: Milagro is aged in American oak, while its Select Barrel Reserve line is rested in both American and French oak barrels.

Aceves says Herradura uses 55-gallon barrels that are replaced every nine years. “The smaller the barrels, the more wood on the product.” Longer isn’t necessarily better when it comes to aging the tequila, though. “If aged too much, you lose the cooked agave flavor,” he notes.

The choice of capacity size changes the level of wood contact, regardless of the type of oak is used. Casa Noble uses three barrel types, with capacities of 114-, 228- and 350-liters, with middle level of toast and no char, with the reposado aged 364 days and the añejo two years.

Hermosillo says the key for him is the blending of the three types of barrels. “Blending will give you the complexity and three dimensionality into your tequila. Some barrels will give me more spice, some more fruitiness, some more chocolate and vanilla and that way I can play and really create the profile we like.”

The bulk of his aged expressions come from the 228-liter size, which he says contributes the brand’s benchmark vanilla, chocolate and almond sweetness. The largest size is next, with its fruit notes, while the 114-liter barrel adds the classic French oak spiciness.

Other Factors

As the tequila market expands and distillers stretch beyond the traditional, a second barreling is becoming more common. Herradura has offered a double barreled reposado, and last fall Lunazul did the same, aged first in American white oak barrels and finished in 11-year-old wheated Bourbon barrels hand-selected from Heaven Hill. After the second aging, the reposado is married with select extra añejo, creating a smooth and sophisticated Tequila, says Reid Hafer, senior brand manager, Lunazul Tequila

Herradura has gotten attention for its limited release reserva reposado finishes, with wood previously aging port, Cognac and Scotch released so far.

And then there’s the impact of weather. Some companies control the humidity and temperature in their warehouses, reducing the evaporation, as well as the flavor and color exchange between spirit and barrel, Rodriguez says.

“The problem is you might age for a year in these conditions, where the angel’s share will be three or four percent but the exchange between tequila and wood is also less, whereas when things are not controlled, you may have 10 to 12 percent evaporation and more extraction of the components of the wood,” he adds

Controlling warehouse environment, like carefully selecting barrels from different locations for different flavor attributes, is as costly and exacting as choosing and monitoring the barrels once they are filled. And as more tequila producers take greater pains to fine tune all the components of the marriage of wood and spirit, the results will likely be more expensive, but also much more interesting.

Jack Robertiello is the former editor of Cheers magazine and writes about beer, wine, spirits and all things liquid for numerous publications. More of his work can be found at www.jackrobertiello.com.